Sometimes I just have to marvel at the creative pace that was kept by (forced on?) recording artists in the ‘60s and ‘70s. I’ve talked about it before with The Beatles and The Animals — a few years past their peak output, Elton John was doing very much the same. His first album was released June 6, 1969. His sixth studio album (discounting a live album and a movie soundtrack!) was the first album I ever bought, “Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only the Piano Player,” which came out January 22, 1973. So what does an artist who has burned through seven albums’ worth of material in three and a half years do next?

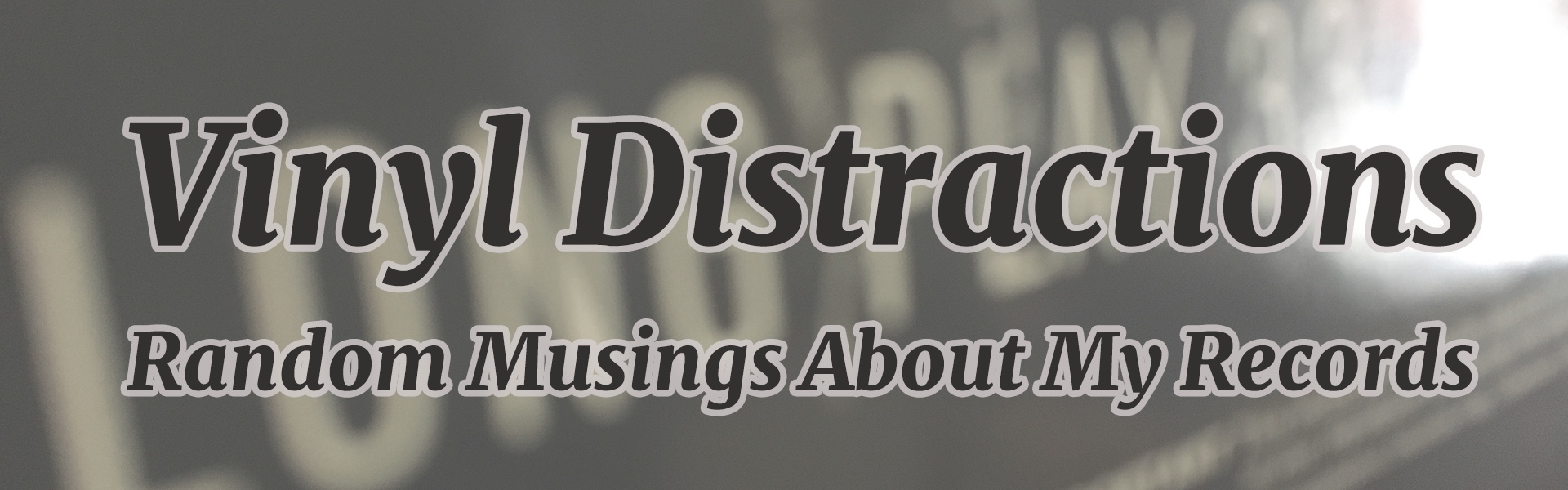

In October 1973, he releases the absolutely epic double album, “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road.” Wikipedia says that Bernie Taupin wrote the lyrics in two and a half weeks, and that Elton wrote the music in three days. The ability to create such disparate work (albeit across a general theme of nostalgia) in anything like that kind of timeframe is simply mind-boggling. Ahh, to have that 26-year-old energy.

This came out in the fall of eighth grade, a school year that was, for me, extraordinarily bleak. As I’ve mentioned before, I didn’t really get into listening to music until seventh grade — music simply wasn’t part of our household. That was a problem, because I loved music. I wanted to make music, and was good at violin in elementary school, but received essentially no encouragement. When my violin teacher retired and was replaced by someone who gave me the creeps, I asked to switch to band. (Hey, momentary aside for parents of the ’60s: when your kid who is really good at something and loves it suddenly decides he doesn’t want to do it anymore, maybe ask why. Same for you school teachers.) So I was moved to band, now two years behind everyone else. What did they assign the kid who regularly missed school because of severe asthma attacks? The tuba, of course. I don’t think I finished the year on that. So I didn’t get to make music.

But come seventh grade, and the gift of my own AM clock-radio, and suddenly I was listening to music all the time. (I’d had little transistor radios before, but they never caught on with me.) To this day I cannot understand how anyone can get through a day without actively listening to music, but in my house, my interest in the hits of the day was met with constant demands to turn it down. Or off. Off would be good.

At that time, listening to music was complicated. We lived in what had been until just a couple of years before, a two-family house. When the tenant upstairs moved out (or maybe died), my parents bought the house from their landlord and set about renovating it — a complete tear-out, down to the studs. Unfortunately, done as an after-work project, and without any spare money, that took years. In the meantime, I was sharing a tiny bedroom with my sister, who was six years younger. There was just room for bunk beds, dressers and a pair of wardrobes in that little room. (I still considered myself fairly fortunate; among my friends, I knew five brothers who slept in the same attic bedroom, and they had to go through the sixth brother’s room to get there.)

So listening to music in private was not something that happened much. In addition to my little clock-radio in my bedroom, there was a Panasonic console radio/record changer with built-in speakers. It was a sleek little walnut unit meant to sit atop a credenza or some such, about 8” tall, maybe 28” wide, and not quite as deep as a record — there was a slot in the back for the record to overhang. It had one auxiliary input and no real way to connect to external speakers, and its output was probably 20 watts. Maybe 15. This was what I had to play records on, and it was in what I guess we’d call a family room; all the other rooms in the house connected to it. And it was in that room that the stereo sat, so that was where I had to play my records — in a room that connected to all the other rooms. Other than a lack of privacy and an ability to just be alone and enjoy them, this wasn’t much of a problem — my records weren’t screaming rockers. I was listening to pretty middle of the road stuff. And my parents didn’t pay much mind to the music as long as I was playing it at sub-detectable levels. Mostly I played it when they weren’t home.

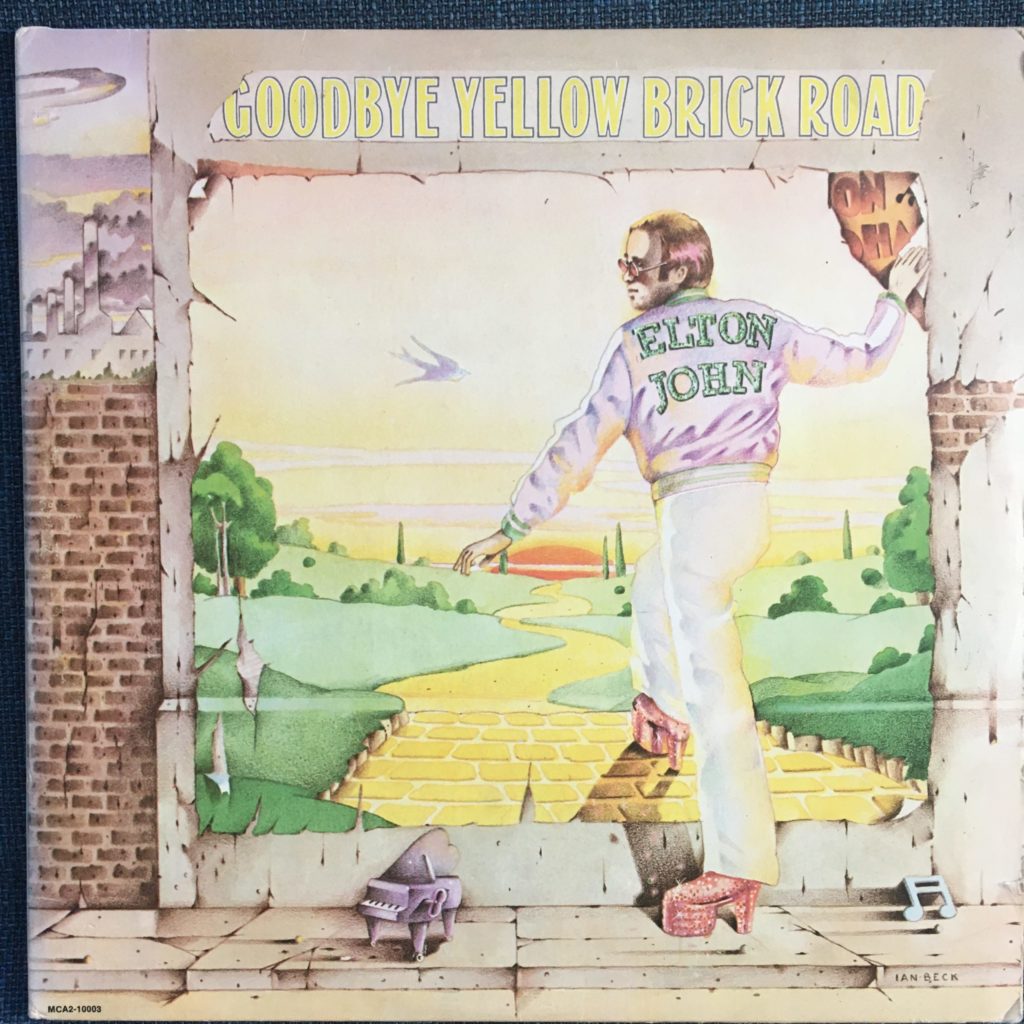

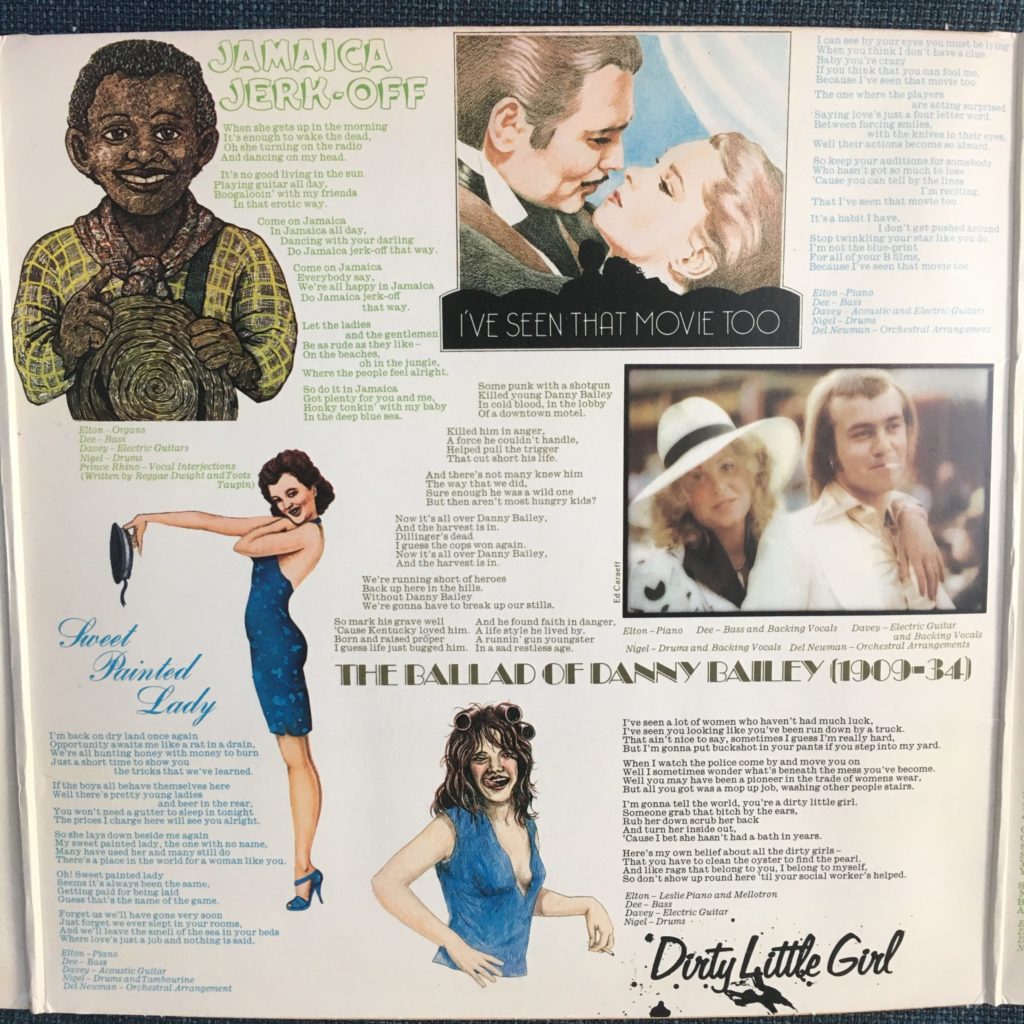

And then I brought home “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road.” And then I played it out loud one day when my mother happened to be home. And then, all of a sudden, she was paying attention, and grabbing the record jacket from me, and demanding to know what I was listening to. Why? The phrase “Jamaica Jerk Off” apparently caught her attention. Even though I know what that meant, I didn’t take it literally — the song wasn’t, to me, about masturbation. To my mother, of course, it couldn’t be about anything else. I was in desperate fear that my precious Elton record was going to be yanked away from me. My explaining that the phrase just meant goofing off also required that I not acknowledge knowing what the phrase really meant. I must have pulled it off, because she walked away willing to let me keep the record, and I made sure never to play that side when she was around, ever again.

Theydies and gentlethems, that is as close to a discussion about sex as my parents and I ever got. (I’m still waiting for “the talk.”)

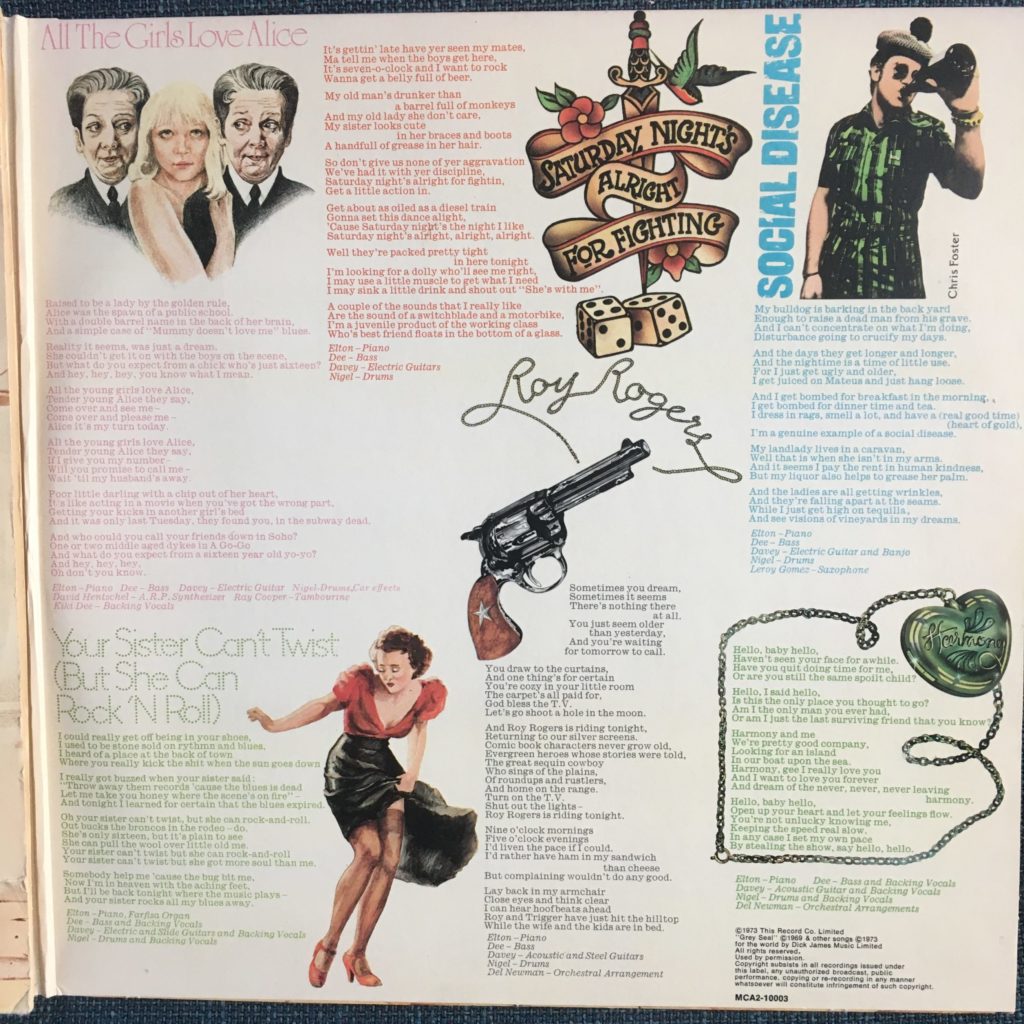

If she was alarmed by the use of the phrase “jerk off” in a song title, imagine if she’d found out what the rest of the album actually contains. There are prostitutes, dirty girls, and lesbians (underage lesbians at that). There’s a song called “Social Disease,” which at the time was code for “venereal disease,” which was ‘70s for sexually transmitted disease — and yet, the song is about alcoholism. “Jamaica Jerk Off” was the least that was going on on that album. There was a lot for a 13-year-old brain to process.

GYBR back cover

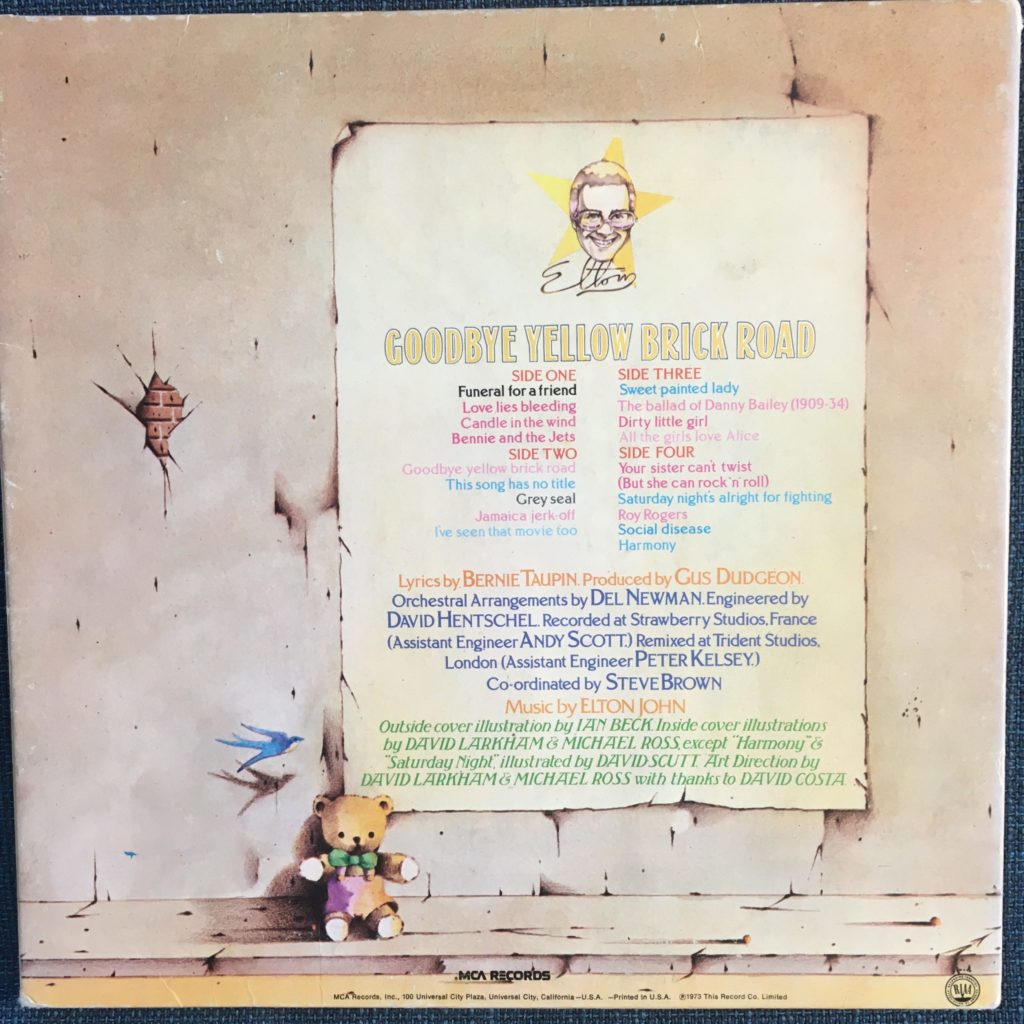

GYBR lyrics panel 1

GYBR lyrics panel 2

GYBR lyrics panel 3

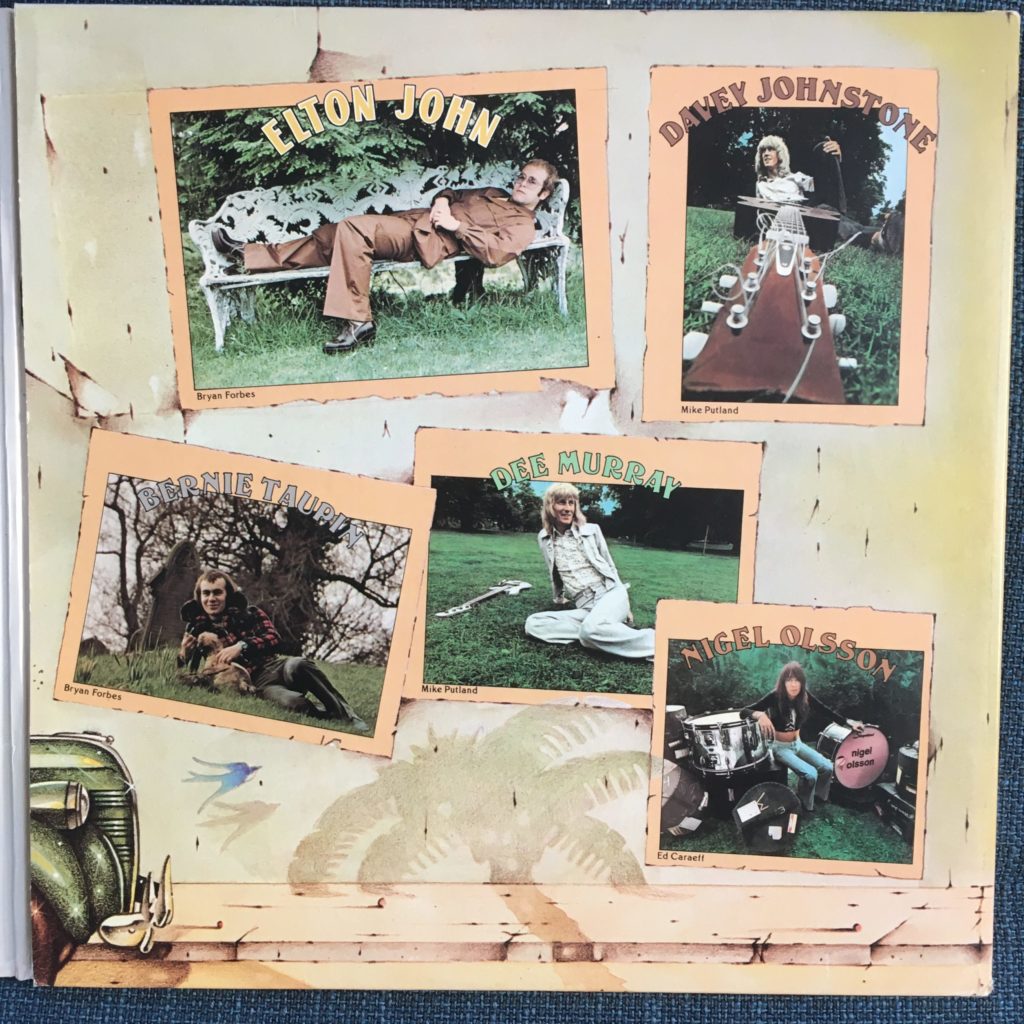

GYBR personnel photos

Goodbye Yellow Brick Road MCA rainbow label

The album packaging included art and lyrics for every single song — mostly beautiful art at that. It really gave you something to stare at as you listened to the music. And these songs are almost entirely great (and the ones that aren’t great? Pretty good). As with his previous album, I studied this religiously. It was among my earliest albums (probably within the first 7 or 8), and despite many, many plays on bad equipment, the vinyl still sounds pretty good. Although I bought this on CD years ago, I have always preferred the vinyl version, just because it’s a great album to look at, and you just don’t get that same feeling from a CD booklet.

So, that’s the story of my pathetic eighth grade existence. It would get better.