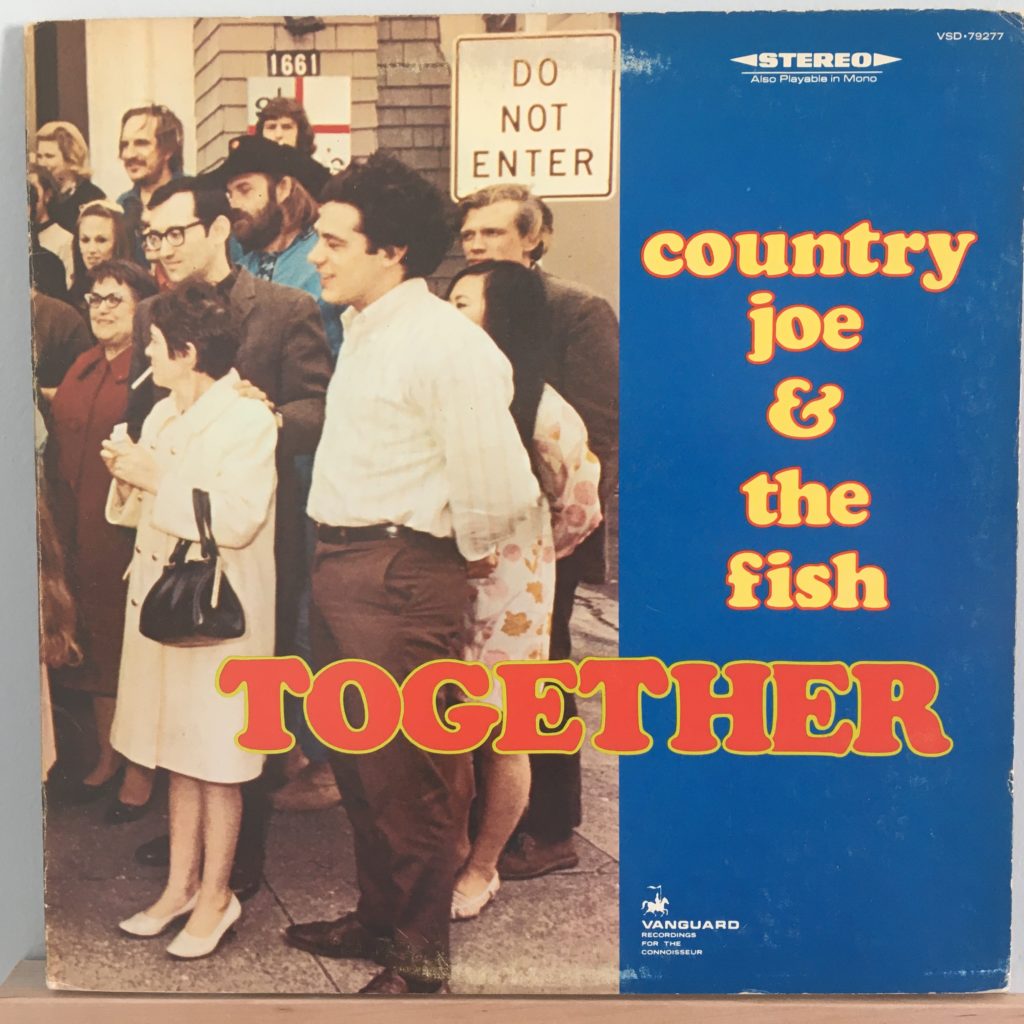

Country Joe & The Fish – Together

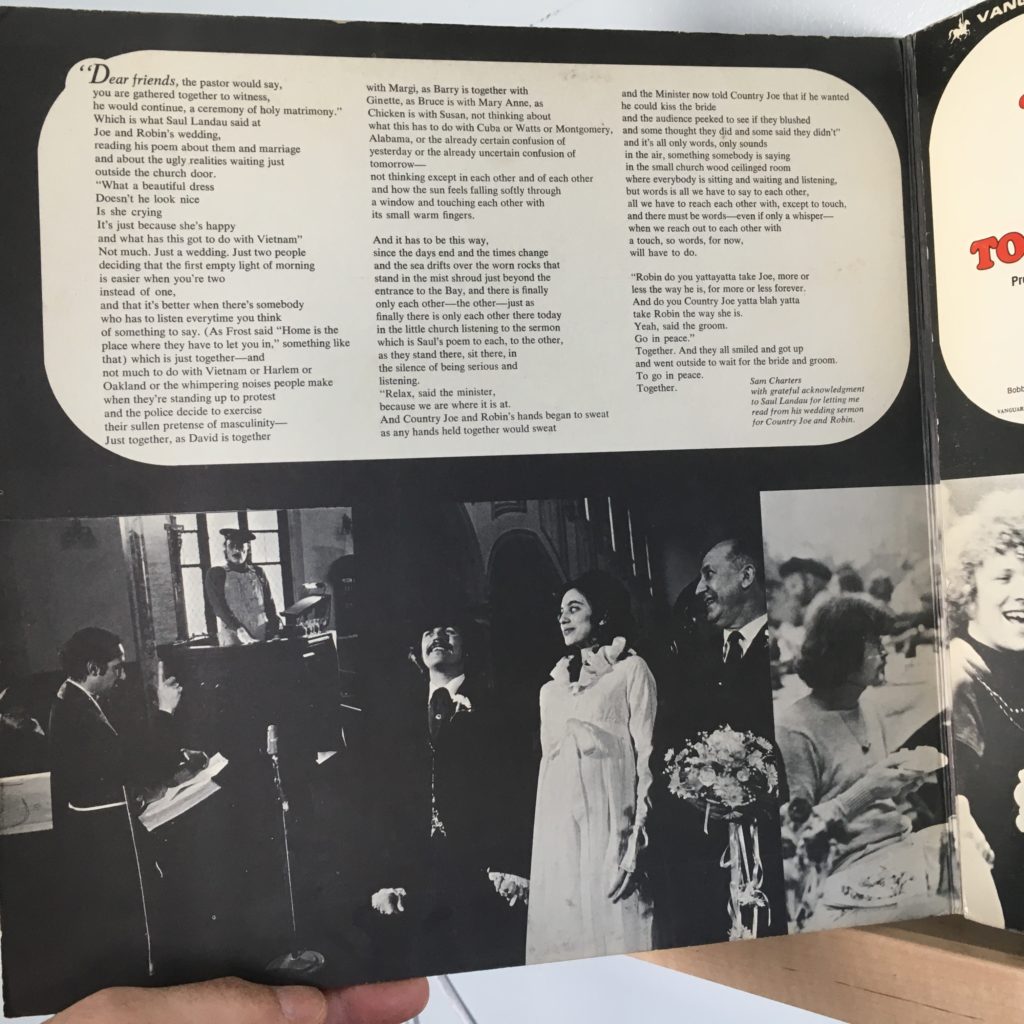

Their third album, released in 1968, is apparently somewhat ironically titled. It was begun as a Country Joe-less effort by just The Fish, but then Joe McDonald rejoined the band. Still, most of the songs were written by Barry Melton and Chicken Hirsch, and the ones that weren’t are, largely, hard listens. Most of the group would quit in the months after the record came out — before their big turn at Woodstock. This was one of the first two albums by the group that I bought, a great find from a garage sale that changed my life, musically.

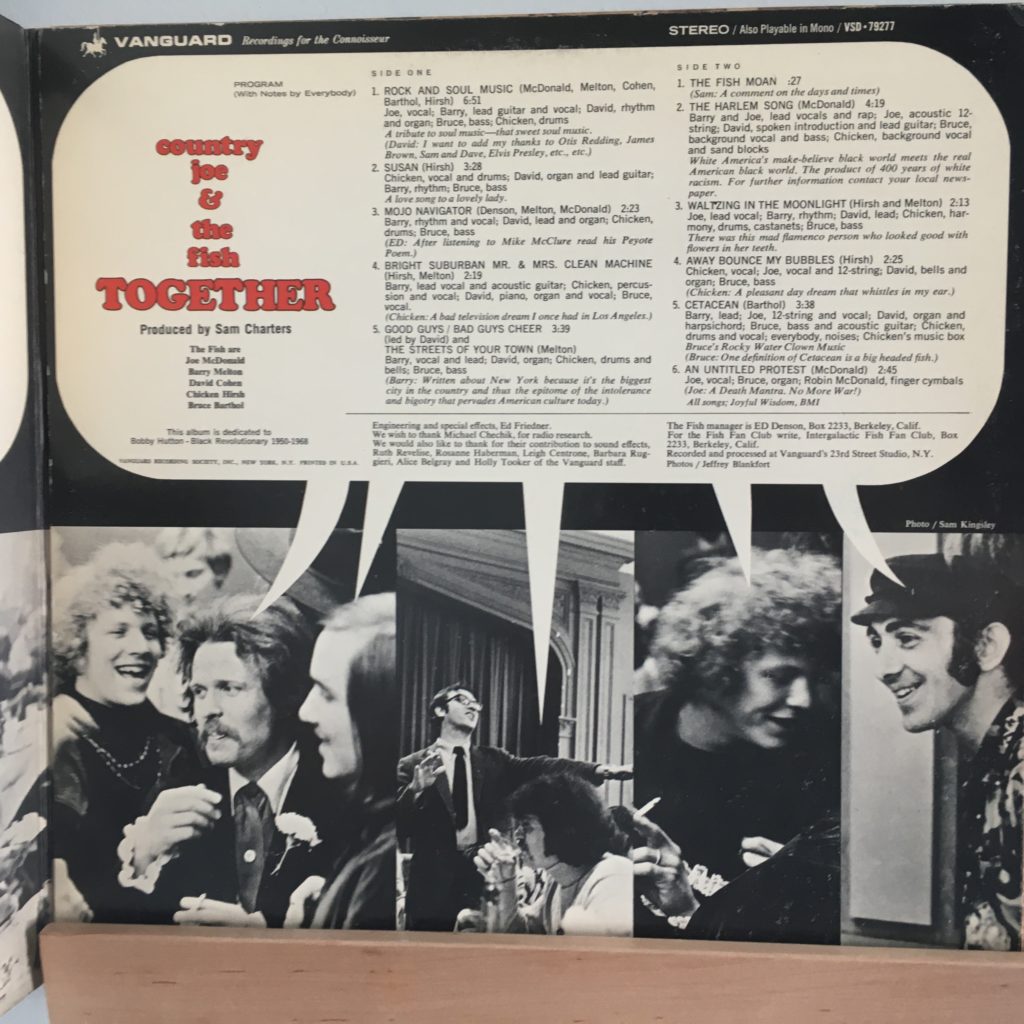

It starts out strong with a somewhat unusual (for the band) soul riff called “Rock and Soul Music,” which the whole band is credited with writing, which proclaims them as the purveyors of this new mix of rock and soul. It’s a good song, but there isn’t another example of the style on the record, so the proclamation seems a little empty. The next songs are more along the lines of traditional Fish material, psychedelic and a little satirical. McDonald’s first big contribution is on side 2 with “The Harlem Song,” which combines old-timeyness (again) with a satirical poke at how white people looked at Harlem as a tourist destination of sorts, even then, but this doesn’t age well, it must be said. In a more sensitive time, it’s a hard listen. And his second contribution is a dirge (“An Untitled Protest”), dirgey as a dirge can be.

I love the track listing inside, however — for each track there’s at least a little blurb about the song.

The album is dedicated to “Bobby Hutton – Black Revolutionary 1950-1968,” sadly showing that some things haven’t changed much in 52 years. One of the original Black Panthers at age 16, Hutton was murdered at 18 by Oakland police after taking part in an ambush of police in the tensions following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Given that Country Joe and the Fish, formed in Berkeley, were deeply involved in Bay Area political protests, their support for Hutton isn’t much of a surprise. Joe’s line in “An Untitled Protest,” “And we send cards and letters” should have aged into irrelevance now; instead it’s more relevant than ever.

It used to be hard to think of what scary, turbulent times those were to grow up in — I wasn’t even 8 in the summer of ’68, and my little ears were being reached by those echoes of unrest, black rage, white fear, Vietnam, and the thought that our country was doing very much the wrong thing in a number of ways. Protest music and psychedelic music were both a reaction to that turbulence , a powerful force for change. And while change needs driving forces, I used to think that over time, if we just waited, the people who carried those old attitudes would just roll off the planet, and something like enlightened people would take their place. Forgive me, I was young. Now I’m old and confused about how we’ve come to this state of affairs, where black men are killed for being black, where those who pretend to love the rule of law applaud the dismantling of our government, and where some days it’s clear how hollow the promise of our society is. Sometimes I blame the hippies and the “do your own thing” philosophy for the rise of a society where the only thing that matters is what you’ve done for yourself, where protecting the weak is just too much of an imposition, where guns are being waved at a virus. And where race is still a central issue dividing us.

And we send cards, and letters.

Things We Said Today